How to collaborate for change: the Youth Homelessness Project

Elise Jorgensen and Amber Lee sharing their work with the Social Design Academy Community

Systems cannot change without people coming together.

There can be few examples more powerful than the Youth Homelessness Project in Perth, Western Australia, which started with three individuals joining forces from three organisations: Elise Jorgensen of Mission Australia, Si Lappin of Vinnie’s and Amber Lee of Indigo Junction.

“The desire to work this way was born of frustration,” says Jorgensen. “We wanted to move beyond organisations positioning themselves in a competitive market.”

In a first, the trio formed a cross-organisation team and enrolled for ThirdStory’s 8-month Design Academy 2024, which kicked off in February. Since then, their project has grown into an impactful movement, a collaboration which spans the whole youth homelessness system, including the Office of Homelessness. It has resulted in the formation of a Youth Rough Sleepers Coordination Group in April 2025 which meets fortnightly and, through collaborative case management, has already found safe, appropriate accommodation for a number of young people. The project is also making strides in the collection and application of data and evidence, and Housing First advocacy for children and young people.

Reflecting on what has been achieved by mid-2025, the team said they simply would not be where they are without the Design Academy; acknowledging that beyond knowledge and skills, it gave them a reason to come together, dedicated time to work on their project, and valuable bespoke coaching to navigate such challenging work.

Travelling at the speed of trust

While the organisations supporting them were distinct - one national (Mission Australia), one faith-based (Vinnie’s) and one local, place-based (Indigo Junction) - the three individuals shared the same level of ambition and commitment. Their stated aim was no less than “to solve child and youth homelessness”.

They all knew that their work together would stretch far beyond the span of the Design Academy program. “We committed to being together outside of the project and working on things face-to-face,” says Lee.

She and Jorgensen had worked together previously, Lee had connected with Lappin at a conference. “You have to allow more time for the relationship- and trust-building, than you would when you’re already with colleagues,” notes Jorgensen. Those early moments as they became a team were vital, knowing everyone involved had to leave egos and logos at the door: “We shared vulnerability around who we were and the way we wanted to work, and what was important to us, our hard lines and our soft lines,” says Lappin. With this grounding, the group was able to draw on each member’s particular “superpowers”: “Elise and I are very passionate, we talk a million miles an hour,” says Lee. “Si would really ground us and say, ‘Let's write some of this down’.”

Their priority was to become “immersed in the voice of lived experience”, says Lappin, to discover more about the young people and their experiences as well as those of front line workers. As with their own relationship-building, they realised that this process could not be rushed. “You have to travel at the speed of trust,” says Lappin.

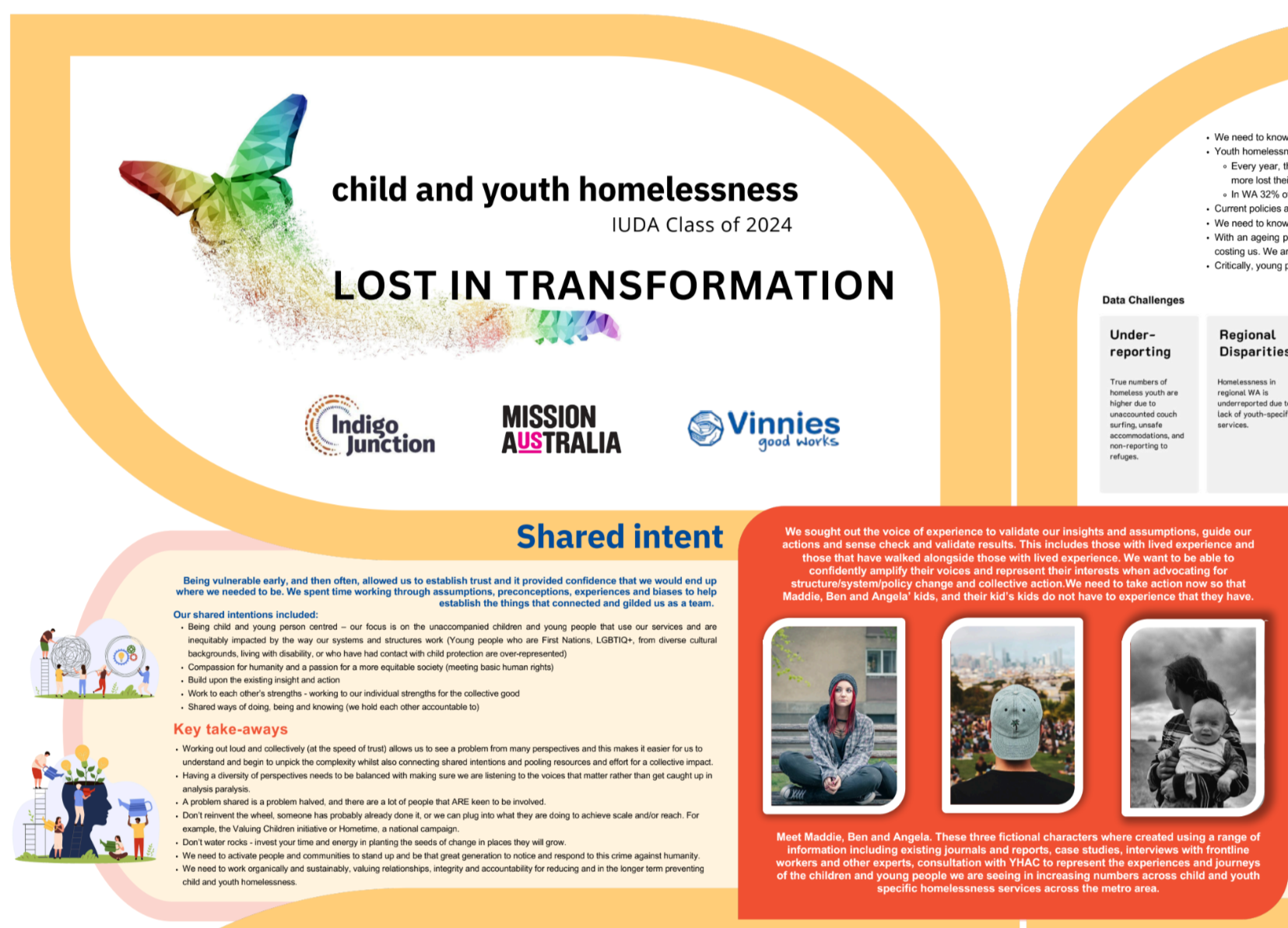

An extract from the poster shared by the team at the end of the Design Academy program.

Learning with the Design Academy

During the Design Academy program, the three learned skills that they immediately applied to their work. What they heard in their interviews with young people experiencing homelessness was synthesised to form the basis of personas capturing the young people. Their stories revealed vividly how vital connection was. “Homelessness is a symptom that someone has become untethered from their connections and their relationships,” says Lappin. “Losing a sense of belonging goes hand in hand with losing a sense of hope.”

Jethro Sercombe, ThirdStory’s Director of Innovation Practice and the team’s coach throughout the program, encouraged them to slow down and not rush towards answers. “Being ok with not having the solution is something that I really struggled with,” recalls Lee.

They found more clarity as they mapped their systems and identified the levers for change. “That was where I had a real a-ha moment,” says Jorgensen. “We need to start with ourselves, because we are all part of that system. What do we have control over? What can we influence?”

Collaboration is contagious

The team’s spirit of collaboration did not stop at the three of them. It has “rippled out throughout the whole project”, says Lee, as they have drawn in more collaborators. She describes their first workshop, gathering people from sector organisations, peak bodies and government, where they shared the personas and journey maps from their project. “Looking out at everybody that was in the room, hearing how passionate everybody was, that was a big moment. I felt, ‘We really have something here’.” Outside these larger engagements, they also had many one-on-one conversations which could be challenging.

“There was a resounding willingness to come on this journey with us, even though we didn’t have really clear projects,” says Jorgensen. Those who gathered formed groups around three focus areas - the prototyping of a Youth Rough Sleepers Coordination Group, data and evidence, and Housing First advocacy for young people.

They credit their success in bringing so many people with them to their clear acknowledgement of all the work that has come before and is continuing in the sector. “It was there in the research, the mapping… We didn’t come in and say ‘we know everything, we hold everything”,” says Lee. They looked to build on positive work already happening, such as the Youth Affairs Council of WA’s (YACWA) Housing First advocacy.

Bringing people together was just the start of the work - continuous trust-building between different groups has been essential to move forwards. Jorgensen describes the importance of having non-judgemental conversations with crisis accommodation services to be able to access data around young people being turned away. “We needed them to trust that we weren’t going to use that to penalise their service. It was about gathering a deeper understanding of our current system.”

Lee describes how a key part of the work has been making the cross-sector meetings for the Youth Rough Sleepers Coordination Group a safe space for people to say “we’re struggling”. Within that context, staff from different organisations can start bringing their resources and skills to take on tough challenges together, for example, when placements break down and young people re-enter homelessness.

Sustaining change

While it is clear how important this team of three has been in creating the conditions for and driving this work, the aim has always been to build “a sustainable movement of collective action”, as Lappin put it. “We didn’t want to hold on to it. It’s not about us,” adds Jorgensen.

The momentum continues to gather as they share the story of their work as widely as possible. It carries a simple, powerful message. Says Lappin, “If you have good humans around the table, who are accountable for the way they show up, and you have a solid process, then good stuff’s going to happen.”

In November 2025, the team delivered a powerful Pre-Budget Submission, resulting from their collaborative and coordinated work to gather evidence across the sector and shaped by the voices of young people with lived experience of homelessness and housing insecurity.

It sets out five urgent priorities to respond to the crisis level of homelessness among children and young people in WA:

Commit to co-designing a costed housing first for youth (HF4Y) model

Invest in a variety of accommodation and housing models for unaccompanied children and young people - including an expansion of Youth Foyers

Strengthen prevention and early intervention initiatives

Increase the capacity of the youth homelessness sector by funding a youth advance to zero project

Invest in the value of lived experience

Read the full submission here

Support for the Design Academy has been provided by Meshpoints which exists to build a stronger culture of entrepreneurship and innovation in WA.

Interested in joining the Social Design Academy? Read more here